Culture: Evolving approaches to embedding and assurance

New report examines cutting-edge developments in the auditing of culture

Download the full report (pdf)

Executive summary

Boards and senior management have the prime responsibility for defining and analysing organisational culture by promoting the values and the behaviours they wish to see across their organisations.

Boards need assurance that a culture of learning from mistakes, rewarding the right behaviour and systems and processes that produce the desired behaviours are being embedded across their organisations. A statement of values is not sufficient on its own; boards need to know that ‘espoused’ values are the same as actual values on the ground. Providing assurance to boards around values on the ground, however, is just part of the picture as culture is not merely the articulation of an organisation’s values.

The use of gut feel can play a part in the audit of culture but in the digital age, assurance providers can make much greater use of hard as well as soft indicators to reduce the subjectivity of their findings. Data from internal reporting systems can be aggregated and used to identify trends and reveal issues of which the board may be unaware. The emergence of ‘big data’ provides scope for internal auditors to develop specific skills and work with data analysts to provide insight.

Who owns culture in an organisation is an issue that boards and senior management need to resolve. It is unclear, otherwise, whom board committees charged with cultural issues should turn to for advice and guidance.

Internal audit is one of the assurance providers that boards and senior management have turned to with some success; but there is still a long way to go. The positioning and reach of internal audit and the ability to ‘tell it how it is’ are as important as the ability to audit cultural issues. Its role as the inside-outsider is the key to success when providing culture assurance. But audit committee members and senior executives must be open to the idea that, at present, there may be less hard evidence compared to more traditional audits and accept the likelihood of grey areas with differences of opinion. This may entail a change in culture and behaviour at the audit committee itself.

Done well, internal audit has a key part to play in assuring boards around culture. But this should not be confused with the idea that internal audit should be the board’s sole assurance provider. This is because internal auditors need to have much more than the traditional skillset to succeed in this area. Furthermore, others have a role to play in embedding and assurance. It is critical for internal audit to have strong relationships with other functions across the organisation.

The approaches to providing assurance around culture are evolving: and some promising examples of new approaches are beginning to emerge. But this is the beginning, rather than the end, of the process. Internal auditors, like all other functions involved in the management and governance of organisations, have much to learn if a step-change is to be achieved. For its part, the Institute is committed to supporting the collective effort.

Against this backdrop, there is much work to be done – for internal auditors, for audit committees and boards, for senior management teams, and others. In particular, we recommend:

- The board should articulate the expectations around values and behaviours and should seek assurance that staff at all levels are effectively ‘living the values’ that the board deem are conducive to a healthy organisational culture.

- The board and the HIA should review whether it is appropriate to incorporate into the audit plan the better use of available data and technology in relation to culture assurance, in addition to traditional surveys, interviews and observations.

- The board and the HIA should review the skill set of the internal audit function, and make provision for any deficiencies to be addressed, as required by the HIA and the audit plan. Where organisations have the resource to do so, this may involve including internal audit in a multidisciplinary team working on cultural issues.

- Boards should try to embed a ‘just culture’ which distinguishes between: simple mistakes/errors; risky behaviours; and recklessness. A ‘just culture’ promotes and atmosphere of trust but makes clear where the line must be drawn between acceptable and unacceptable behaviour.

- The audit committee should encourage the HIA to sit as an observer on various senior-level boards and committees and key project steering groups. This enables the HIA to glean insight into organisational behaviour and culture through being able to see and hear not only what is being discussed but also the way it is being discussed.

- HIAs and boards should agree to make space for a ‘meta-audit’ i.e. the chance for the HIA to stand back and think about what the experiences of all standard audit activity say about culture.

- Internal audit needs to be conscious of its own culture/behaviours and how it is perceived by the rest of the organisation. Internal audit should audit its own culture to help convince others in the organisation of the value of its involvement.

- HIAs should engage with those functions that are involved in the embedding, enforcing and assessing of culture to reduce the risk of gaps or duplication of work. The board and senior management should support this.

HIA culture survey results

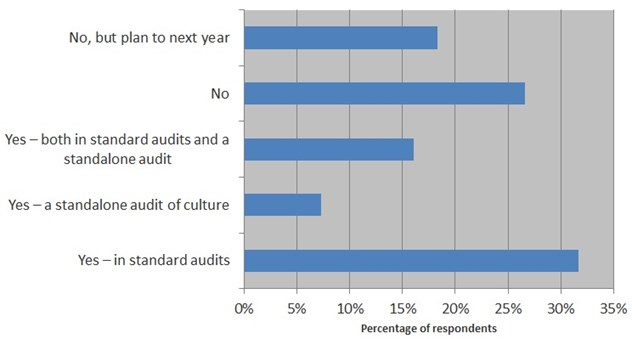

In November/December 2015, we conducted a survey of heads of internal audit (HIAs) from all sectors of the economy, to collect factual data on the extent to which the profession is involved in auditing culture; the methods they are using; who else they are working with; and how they are reporting on issues raised.

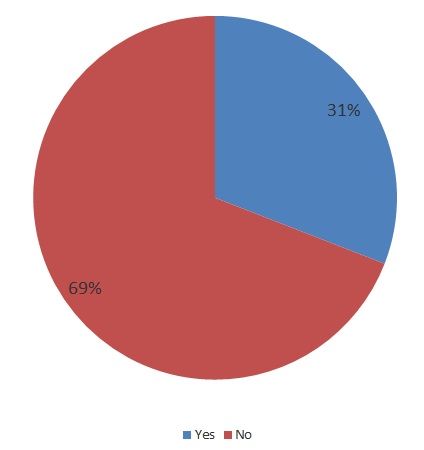

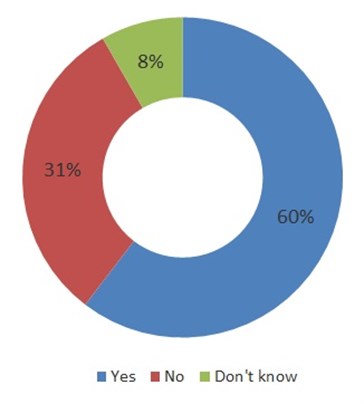

Does your audit plan include any aspect of culture either in your standard audits or as a standalone audit of culture?

Has your board established and articulated what culture it wants?

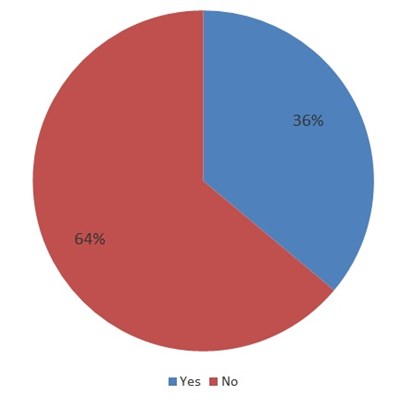

Have you been asked to assess the extent to which the company’s values are manifested in the behaviour of all staff in the organisation?

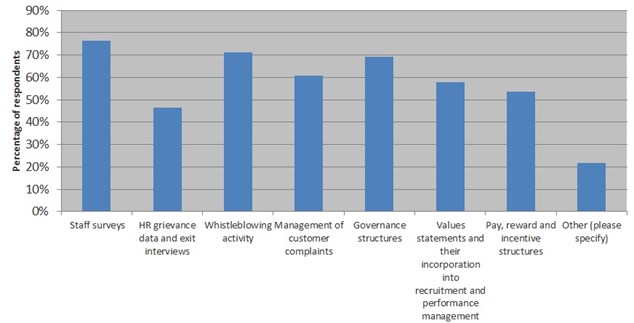

Which of the following do you use as proxies for auditing culture? (tick all that apply)

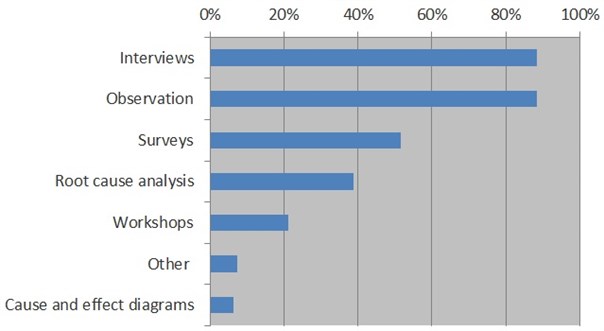

What methods do you use to audit behaviours and culture? (tick all that apply)

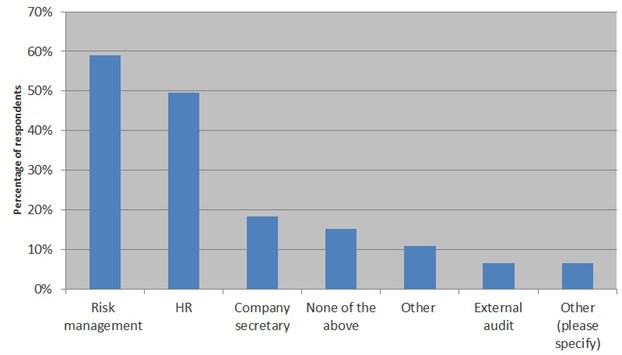

Do you work with others in the area of culture? (tick all that apply)

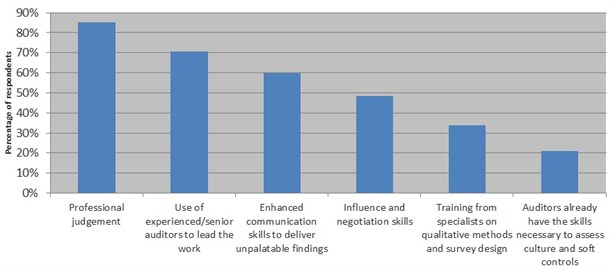

What skills and competencies does internal audit need to audit culture and in particular soft controls? (tick all that apply)

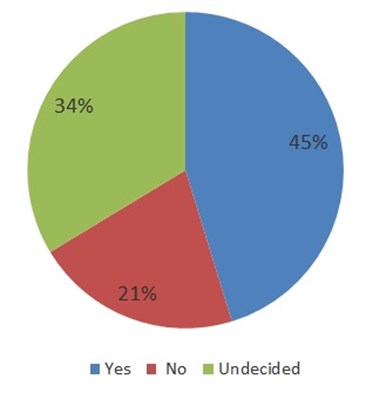

Do you believe that bringing a multidisciplinary team together, including e.g. organisational psychologists and staff from operations, would enhance the quality of participation in and the acceptance of audit findings?

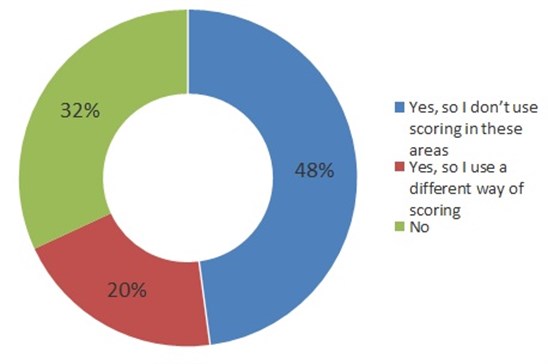

Do you think “scoring” departments/functions on areas such as management and leadership, teamworking, ability to speak up, learning and problem-solving hinders future audits?

Do you believe that the more sensitive reports in this area need to be submitted to the audit committee chair only in order to ensure the change is supported and carried through?