Auditing supply chains

This guidance provides an overview of different approaches for auditing the topic of the supply chain. It includes ideas for breaking the subject down into manageable chunks, describes some of the risks that can be refined and developed, and looks at some of the assurance options in a little more detail.

For internal auditors new to the topic there is also an introduction to supply chains.

Supply Chain Assurance

Deciding what to audit, when and where requires an understanding of the risk profile of the organisation, discussion with senior management, supply chain professionals and risk managers, as well as consideration of other sources of assurance.

Supply chain risks increased in profile following the COVID-19 crisis as organisations grappled to manage its impact on product availability and production; this is unlikely to diminish with the transition to a low-carbon economy and pressure to adapt to climate change.

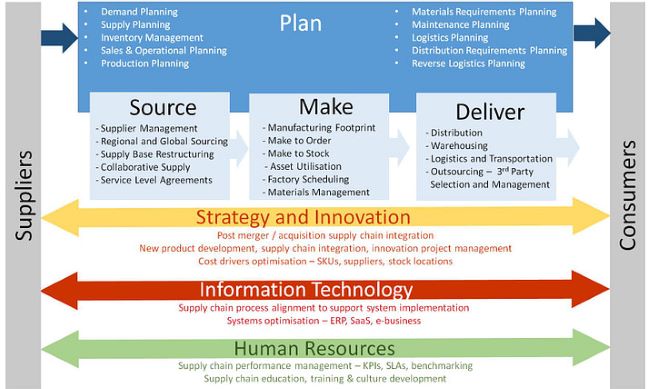

As shown in the diagram below, there are many discrete operational processes that combine to form the overall supply chain in addition to the more strategic aspects of supply chain governance and management. Auditing any of these topics can be classed as providing supply chain assurance.

Image reproduced with kind permission by Enchange.com

Three Lines and internal audit assurance

The Three Lines Model (formerly three lines of defence) is particularly relevant to the supply chain and the role of independent assurance. It is a useful tool when creating the audit plan and also when defining an audit engagement scope.

Internal audit should discuss the extent of assurance with operational managers (first line) and other assurance providers (second line). By coordinating activities, it is possible to maximise the overall use of limited audit resources to avoid duplication and/or gaps.

For instance, it may be a better use of internal audit’s time (third line) to consider and support the assurance work of others rather than directly auditing the same risk areas.

One example might be to initially examine the reliability that internal audit can place upon management’s supplier vetting and assessment processes. Followed by some ‘lighter touch’ internal audit work to verify established, risk mitigation and risk appetite levels, remain effective.

However, we should not underestimate the scale of this task as it is likely there will be a variety of assurance providers adding support to the supply chain by undertaking reviews at various points. This can include ISO accreditations for quality, environment, health and safety and IS security as well as the work of compliance, customer services, human resources, legal and regulatory, risk management etc.

While assurance is obviously important, there is a need to minimise cost and to avoid business units being overburdened with ‘audit’. Consequently internal audit is well positioned to present a case for mapping and coordinating assurance (a requirement of Standard 2050) against significant supply chain risks.

In the absence of a formal mechanism internal audit could initiate a coordinated approach through regular discussion with and review of other assurance providers.

Supply chain maturity

The size and complexity of an organisation will often influence its maturity; along with the availability of funds to invest in technology which is a key driver.

Internal auditors need to acknowledge where the positioning of their sector, organisation and its aspirations are in order to provide assurance at the right level.

There are many supply chain maturity models produced by Gartner and other firms, together with software providers. We have combined some of the key elements into one below that is useful for internal auditors; check if there is an alternate model that your organisation has already adopted.

|

Maturity |

Function |

Focus |

Enabler |

|

Reacting |

Task |

Respond to demand |

Spreadsheets, basic software |

|

Anticipating |

Process |

Balance supply and demand |

Utilise systems and IT, continuous improvement |

|

Predicating |

Internal enterprise |

Optimise planning for profit |

Outsourcing, silo proficiency, source talent |

|

Collaborating |

Extended enterprise |

Partner across the supply chain for value |

Measure, reconfigure, integrate and optimise IT |

|

Orchestrating |

Virtual/digital network |

Re-engineer for agility to navigate uncertainty |

Digitalisation, network, redesign/rebuild |

Where risk management is less mature across the supply chain internal audit is in a position to provide advice and insights through its consultancy/advisory role to help build or develop risk management processes. This role can take several focuses such as: advocating the value of risk management, facilitating risk identification, assessment, and control, fostering thinking about risk appetite levels, assurance mapping etc. We can also apply internal audit consultancy services specifically to the supply chain either through named engagements or as a follow on to assurance reviews.

Supply chain risks

During the planning and scoping of any audit engagement internal auditors must establish which risks management (first line) has identified that are relevant to the topic. Many organisations will capture risks in registers, documents or on dedicated software. Internal auditors should not limit their scope to these risks but identify risks for themselves where appropriate.

The breadth of supply chain risk is huge.

In no particular order this table provides an insight into some of these, with examples of possible controls.

| Risks | Controls |

| Plan | |

|

1. Insufficient inventory to meet demand. |

Forecasting process and modelling |

|

2. Bias within algorithms skews outcomes. |

Independent validation of input variables Manual sampling of outcomes |

|

3. Scarcity of raw materials reduces output of finished goods. |

Environmental awareness; design adaption, develop synthetic alternatives |

| Source | |

|

4. Loss of key supplier impacting availability of finished goods (insolvency increasingly likely during recession). |

Supplier relationship management Financial viability assessments Critical points of failure – substitutions identified |

|

5. Third parties operating outside expected values and behaviours (for example sub-contractors or suppliers accepting or offering bribes due to local custom and practice). |

Supplier code of ethics Supplier audits Contractual terms and conditions ‘Concerns’ hotline or similar |

| Make | |

|

6. Production or sourcing of poor-quality parts/goods resulting in recall. |

Supplier due diligence/vetting Accreditation to relevant standards Quality control procedures |

|

7. Climate activism targeting manufacturing or logistics sites. |

Stakeholder engagement Environmental targets and reporting |

| Deliver | |

|

8. Loss due to theft/damage of materials and or goods, including piracy. |

Security proportionate to value and risk; tamper proof packaging, security tags on vehicles, armed guards |

|

9. Shortage of warehouse operatives due to consequences of Brexit outcome leading to issues with capacity planning. |

Local recruitment campaigns Remuneration at living wage or higher |

| Strategy and innovation | |

|

10. Breach of competitors intellectual property rights resulting in legal action/reputation damage. |

Product design protocols |

|

11. Macroeconomic fluctuations such as taxation, duties, currency rates, tariffs or labour costs leading to increased fixed costs and/or reduced access to materials. |

Subscription to daily news briefings Strategic reviews |

|

12. Disruption due to new regulations, in particular those relating to climate change. |

Lobbying and engagement with regulatory consultations Innovation incentives for supplier/partners Carbon reduction strategy Waste minimisation strategy |

| Information technology | |

|

13. Cyber-attack; global supply chains are connected by technology, digitalisation including the internet-of-things. |

Network encryption System security protocols |

|

14. Failed implementation of supply chain technology resulting in loss of competitive advantage and wasted investment. |

Specialist project management expertise Appropriate project management methodology |

| Supply chain management | |

|

15. Non-compliance with regulations, in particular overseas frameworks, due to lack of understanding. |

Register of legislation/regulation for all jurisdictions in which the organisation operates Legal advisor validation of contracts |

|

16. Political and/or civil unrest, including strikes and border delays that impede production or delivery. 17. Natural disaster disrupts logistics or production. |

Resilience planning including scenarios and stress testing |

|

18. Siloed processes impact supply and/or demand. |

Defined supply chain governance Training and awareness programme |

Assurance in more detail

As explained earlier, there are many ways of providing assurance. Here is a more detail on some of the possible audit engagements you could undertake to get you started on examining this critical area. Note: all organisations are unique and this guidance is generic for you to adapt to best fit your organisational context.

Supply chain governance

Internal auditors will be familiar with the concept of governance.

The complexity and diversity of a supply chain requires effective governance to ensure appropriate authorities, accountabilities, leadership and oversight.

Assurance across an appropriate and proportionate governance framework ensures that:

- risk appetite is defined, communicated and monitored

- projects and budgets are challenged and approved

- policies, procedures and practices are endorsed

- service levels are defined

- operational conflicts can be surfaced and resolved.

Across the extended enterprise and even within relatively simple supply chains, there is increasing pressure for enhanced corporate social responsibility, ethical stewardship and greater understanding and meeting of wider stakeholder expectations.

The Institute of Risk Management (IRM) explain in their document Extended Enterprise: managing risk in complex 21st century organisations the ‘influencers and shapers’ that boards need to pay particular attention to when thinking about risks and risk management for an extended supply chain.

Influencers

Governance - Organisations in the extended supply chain will have different attitudes and approaches to risk management. It is important for risk management to have a profile under a broadly common approach with strong commitment from leaders.

Information - Access to information about risk responses is critical to understand that quality and control is up to expected standards.

Regulation - Different regulatory environments can make the management of risk much more complicated. Understanding the nature and scope of how regulators might influence the various participants is important.

Shapers

Incentives - Incentives in each part of the supply chain will shape the nature and appetite for taking risks. It is important to understand what is taking place to incentivise or disincentives people in the network.

Ethics - The culture and ethics underpinning the nature of what is right or wrong, acceptable and unacceptable will shape the way governance and risk management are applied.

Assurance - Assurance focused on significant risk to verify what should be happening is happening will shape confidence in the risk management process and influence risk mitigation.

Supply chain management assurance

An audit of this nature can take a relatively high-level approach, particularly if there is a supply chain management function in place. There may not to be sufficient internal audit budget to get into the operational detail of process risks so assurance would be focused towards the ‘glue’ that links the disparate parts of the supply chain together. This could include performance management, internal and external targets/service level agreements, reporting and training. It could also include governance.

Risk management is key to an effective and efficient supply chain.

To identify and assess all its supply chain risks, management need to have a full picture of the process, sub-processes and the myriad of relationships and dependencies. There are many modelling tools available that will support the mapping of the supply chain and choosing the most appropriate one is an art in itself.

Where mapping exists, internal audit can provide assurance that it is current and accurate.

Where mapping does not exist, internal auditors can raise this and highlight the vulnerabilities and threats of not having clarity of the supply chain and visibility of the risks.

Supply chain resilience

Media headlines demonstrate the increasing fragility of supply chains; internal auditors will recall the empty shelves at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic and the government’s scramble to secure PPE and ventilators. Furthermore, the increasing frequency of extreme weather events can impact the availability of raw materials and disrupt logistics.

The MET office summarises research into the frequency and intensity of extreme weather.

Comprehensive resilience assurance encompasses the loss of a critical supplier, a building or facility, a piece of equipment, access to a particular trade route or even a key member of staff.

Climate change is having a profound impact on supply chain risk, and so resilience assurance must attempt to look at both the current, and likely future consequences for different geographic regions and highlight the risks to management.

Refer to the guidance Climate impact within supply chains for more information.

Subcontracting - Nth party assurance

One of the biggest risks within supply chains, as identified in Risk in Focus 2020, is the use of unauthorised outsourcing/subcontracting; a myriad of nth parties.

Subcontracting is a normal part of production. It is primarily driven by pressures on timing, pricing and technical production processes. However, unauthorised subcontracting presents significant risks for supply chain continuity and compliance production standards relevant to quality, environment and social matters.

Internal audit can provide assurance over the controls that the organisation has in place to protect it against unauthorised nth party risk.

Examples of good practice could include:

- establishing factory capacity before supplier negotiations relating to volume begin

- undertaking a gap analysis between factory capacity and purchase forecasts

- awareness of supply chain saturation/dependencies on specific locations

- demand planning controls/procedures (particularly seasonal or unplanned fluctuations)

- sustainable purchasing/sourcing practices

- exploitation of digital technologies to remotely monitor activities

- supplier partnerships to improve standards and capacity.

Conclusion

The breadth of assurance possibilities means that internal auditors must be very clear as to the scope of their assurance to avoid any misunderstanding or risk of false assurance.

Internal auditors have a key role to help their governing body (boards and audit committee) understand the complexities of their supply chains and the importance of robust assurances that they are being appropriately managed. The profile of an internal audit review can be influential in raising awareness of critical risks and facilitating control improvements. The challenge for internal auditors everywhere is to recognise the value that this can offer and to make it happen.

Further reading

Standard 2050 – Coordination and reliance

Outsourced services

Shared services Climate impact within supply chains

The Institute of Risk Management – Extended Enterprise: managing risk in complex 21st century organisations