IT basics for non-IT auditors

Today’s heavy reliance on Information Technology (IT) requires internal auditors to have a basic level of IT knowledge, sufficient to:

- Understand the related opportunities and risks within their organisations

- Ask the right questions of the right parties and draw the right conclusions

|

IIA Global has produced a suite of Global Technology Audit Guidance (GTAGs) And a risk-based approach to assessing the scope of IT General Controls: GAIT for business and IT risks |

This information guidance is designed in three parts to help direct you to the information you need.

|

Part 1: Understanding the language of IT |

Part 2: Exploring IT risk |

Part 3: Getting started |

|

|

Questions for an audit test plan

|

Part 1

This section aims to provide high-level knowledge to enable you as an internal auditor to speak and understand the language of your IT colleagues.

Bits, Bytes and Basics

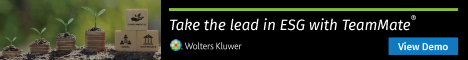

This diagram shows that IT is central to our organisations.

- The outer ring defines typical generic business processing objectives.

- The middle ring indicates the risks to the objectives.

- The inner circle illustrates typical departments developing and operating the systems to enable the objectives.

Overarching this is IT governance: The processes in place to ensure the efficient and effective achievement of the business objectives.

Processed information is known as data. It is stored in bits and bytes using something called binary form. To delve deeper into the details click here.

Differentiating between what you can physically see and touch, versus what you cannot, is key to understanding the basics of IT. Physical devices are known as hardware. Programs (and data) stored on those devices are known as software. The software that controls the computer is known as the operating system (eg, Unix, IBM z/OS, AS/400, Google Chrome OS, Android, Apple macOS, IOS).

Application software handles the day-to-day business processes (eg, customer orders and accounting). This might be developed ‘in-house’ by the organisation’s own programmers or perhaps purchased as a package from a third-party software supplier. Some developers use opensource a model of sharing free-to-use software available via the internet.

|

IA notes:

|

The brain and main memory of the computer hardware sit within the Central Processing Unit (CPU).

Computers process information in various modes, eg:

- Online - where the host computer receives/sends input/output from/to other computers over a network

- Real-time - where the online updates to the host computer system occur instantly as new data is entered

- Batch - where the data input is captured at a point in time but posted to the host system at a later stage.

Many online systems might appear to be real-time, but technically are not, eg, Internet banking systems might show an update to your account directly after the transaction is entered; however, the true update may not take place until the batch processing run, which often takes place overnight.

Computers are linked together (physically or wirelessly) into networks, so that they can communicate and share resources such as data and software. Most organisations use the internet to communicate (eg, between their own systems, staff, departments and regions) and externally (eg, with customers, suppliers and stakeholders).

Virtual Private Network (VPN) technology is increasingly being used as a means of enhancing security when communicating over the Internet. The VPN creates a secure tunnel between locations across the Internet, via an intermediate VPN server, employing dynamic IP addressing and data encryption (disguise) in the process. The use of VPNs can nonetheless be controversial, eg, they can be used to mask location and to inhibit logging (such as by the Internet Service Provider - ISP).

Networks typically incorporate control facilities such as demilitarised zones (DMZs) and firewalls. Generally a DMZs segregates internet servers from the organisation’s internal servers and firewalls are used to monitor traffic to allow or deny progress based on configurable rules.

|

IA notes:

|

Systems architecture brings everything together. It is the term used to describe the overall design and structure of a computer network or system. There are four main components to any system architecture: processing power, storage, connectivity, and user experience. Complexity varies widely depending on the business processing objectives of the organisation and resource availability. It must be flexible enough to meet changing needs; a structure that is too rigid will not be able to accommodate new software or hardware.

|

IA notes:

|

Some organisations run all of their IT in-house, while others outsource the running of some or all of it to third-parties. Most organisations use cloud services operated by third-parties.

|

IA notes:

|

Digitalisation

Digitalisation is an ongoing transformation for organisations. Often known as Industry 4.0. Its competitive advantage was brought into sharp focus by the pandemic.

Blockchain is both enabled by and an enabler of digitalisation. It makes use of internet-based de-centralised processing and encryption facilities, potentially to reduce transaction costs, increase security and eradicate single points of failure (since there is no reliance on a central system/server). Click here to read a technical blog on the topic.

Artificial Intelligence (AI) applications, which are designed to learn from the organisation’s data and ‘think’ like humans, are now commonplace. One use of AI that everyone will have encountered is the chatbot on websites. From a data perspective AI can rapidly interrogate huge databases and is used in a host of environments from online shopping and factory management to money-laundering.

5G (telecommunications technology) with lower latency (response times) and increased download speeds provides services around ten times faster than 4G. In addition to the expected faster operations and enhanced virtual reality applications there is the potential to replace physical wires with wireless connectivity in many locations.

|

IA notes:

|

The IT department

There is no one size fits all for IT functions. The earlier diagram is illustrative.

Likewise, the information below is a guide.

Effective segregation of IT Operations and Systems Development is key to many basic IT controls.

IT controls are part of the first line of the three lines model.

There are valid arguments for and against including areas such as ‘IT risk’, ‘change management’ and ‘IT security’ within IT itself. The solution will depend on the nature and requirements of the organisation. Nonetheless, it is generally recognised that ‘change management’ and ‘IT security’ should not sit within ‘systems development’. Regardless of the way in which IT is organised, the effectiveness of segregation and control is largely dependent on culture, standards and the competence of the IT staff.

|

IA notes:

|

IT management and administration

Administration often supports all areas within IT, particularly those within IT management.

|

Management: Overseeing all aspects of IT staffing, development, processing and governance Budgeting, costing, charging Management reporting (eg, for the board, risk committee, stakeholders, audit committee and regulators) Devising and maintaining standards Recording software/hardware ownership Managing vendors/third parties and related contracts Creation of an information asset register Regularly processing updates / system patches Requesting and actioning third part penetration testing eg denial of service attacks Training |

Risk Identification and documentation of IT related risks Monitoring IT-related risks, in liaison with user management and the risk function |

|

Change management Handling the secure transfer of resources between the development and production environments (and vice versa) Overseeing the controls to ensure that all production software is up-to-date and bona fide |

|

|

Cyber security Overseeing (and to some extent managing directly) the security of the organisation’s networks and systems, including segregation of environments/duties, user access rights, penetration testing (also see Part 2, Cyber Security, within this guidance). |

Operations

|

Operators Starting-up and shutting-down machinery Executing production jobs (input, processing and output) Managing back-up and restore procedures Handling storage devices (eg, disks and tapes) Issuing system commands in the process of the above (eg, to list directories/files, show active jobs, compress/decompress files, copy files) |

Scheduling: Determining the what, why, who, how, where and when of processing jobs. |

|

Network management Handling internal and external telecommunications links (including firewalls and DMZs). |

|

|

PC management Setting-up and maintaining personal computers |

|

|

Database management Handling the set-up and maintenance of the system databases |

|

|

Technical support Setting-up and configuring the hardware and operating systems software (potentially including some basic systems programming duties) Supporting computer operators and users Managing emergencies Writing command language, which enables a set of commands to be grouped into a mini-program Researching emerging technologies |

Systems programming: Maintaining the operating systems software (dependent on the amount and nature of systems programming required, this service might be provided by the third-party operating system supplier or reside in-house within Technical Support, Systems Development or as a discrete function) |

|

User Liaison: · overseeing the day-to-day interaction between IT Operations and the application systems users |

|

|

Technical project teams Handling specific IT Operations projects (eg, the upgrade of an operating system or network component, or the IT Operations side of ongoing Systems Development projects) |

OAT ‘Operations acceptance testing’ - testing the system on behalf of IT Operations prior to ‘go live’ |

Systems Development

|

Project Control Overseeing the business development/change projects |

Project teams (including programmers): Developing, changing and testing application software |

|

Systems analysis Converting user requirements into a specification document for the programmers (like an architectural drawing, for use by builders) |

Systems testing Overseeing the testing of suites of programs after individual program and ‘link’ testing, and prior to UAT |

|

UAT Overseeing the ‘user acceptance testing’ prior to ‘go live’ |

|

Part 2

This section gives you a high-level overview of how risk is managed within the IT function and the relevant frameworks that may be mentioned.

IT risk appetite

Organisations with mature risk management processes will have clear definitions of their risk appetite in all relevant areas, including IT-related risks. IT environments are typically dynamic and volatile. A ‘zero tolerance’ is unlikely to be helpful.

An example of how this could be addressed is to consider the appetite for the failure of the business processing objectives (think back to the earlier diagram):

- 30 minutes downtime for ‘x application’ in a single event

- 70 minutes downtime for ‘x application’ across a rolling 60 day period

- 97% tolerance for batch run’s relating to process ‘x’

It is important that the risk appetite statements enable the IT function and users to operate within a framework of expectations and tolerances. This guides the priority of resources to fix problems as they arise and targets development to improve known issues.

|

IA notes:

|

IT risk frameworks

Your organisation is likely to have a process in place, which it is essential to familiarise yourself with.

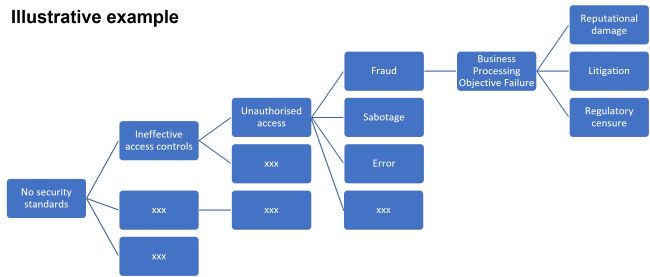

The IPPF defines risk as ‘the possibility of an event occurring that will have an impact on the achievement of objectives.’ A simple model to help you to recognise, express, assess and ultimately contribute to the management of your organisation’s IT-related risks is set out below.

- Identify your organisation’s business processing objectives.

- Identify events which might threaten those objectives.

- Assess the likelihood of those events occurring.

- Assess the impact of those events on your organisation.

Risks are often inter-related, where one can lead to another. This is very much the case within IT.

|

IA Notes:

|

The following is a list of common types of IT risks.

|

Architecture risk IT structures fail to support operations or projects

|

AI risks Misinformation or operations resulting from technologies that learn and self-improve |

Asset management risk Failure to control IT assets such as loss of mobile devices |

|

Audit Risk The chance that an IT audit will miss things such as security vulnerabilities or legacy risks and potentially provide a false assurance |

Availability Risk Downtime of IT services |

Benefit Shortfall Investments in IT that fail to achieve projected return on investment |

|

Budget Risk IT programs, projects or operations teams that exceed budget.

|

Capacity Risk Capacity management failures such as an overloaded network that causes inefficiencies such as a process failure. |

Change Control A failure to control change to complex systems including practices such as change management and configuration management. |

|

Compliance Risk Potential to violate laws or regulations |

Contract Risk A counterparty that fails to meet its contractual obligations such as missed service level agreements |

Data Loss Loss of data that cannot be restored |

|

Data Quality Poor quality data that causes losses due to factors such as process failure, compliance issues, GDPR regulatory breach or declining customer satisfaction |

Decision Quality Sub-optimal decision automation or inaccurate decision support analytics |

Design (Technical) Debt A low quality design or weak implementation that results in future costs |

|

Facility Risk Risks related to facilities such as data centres |

Infrastructure Risk Failures of basic services such as network, power and computer resources |

Innovation Risk Risks associated with research and development, experimentation aggressive rates of change (disruptors). Typically involving novel approaches using agile methods to fail early/fail forward. |

|

Integration Risk Potential for integration of organisations, departments, processes, technology or data to fail |

Legacy Risk Technology that is out of date such that it is difficult to maintain or out of support and the associated risks of failure |

Operational (or Process) Risk The potential for technology failures to disrupt business activities |

|

Partner Risk Associated with technology partners such as service providers – cloud in particular |

Physical Security Related to IT such as at data centres, locks on hardware. |

Project Risk IT projects often have a high failure rate due to a variety of risk factors such as scope creep, estimation errors and resistance to change |

|

Quality Risk Failures of quality assurance and other quality related practices such as service management |

Regulatory Risk Potential for new IT related regulations |

Resource Risk Inability to secure employees or contractors with the appropriate expertise |

|

Security Threats Specifics such as malware and hackers |

Security Vulnerabilities Specifics such as weak passwords and poorly designed software |

Single Pont of Failure A small component (such as a switch or cable) of a large system that has the potential to bring down an entire system when it fails |

|

Strategy Risk Associated with a particular IT strategy, including risk appetite |

Transaction Processing Risk Inability to effect transactions |

Vendor Risk Potential for an IT vendor to fail to meet obligations |

|

IA notes:

|

COBIT (Control Objectives for Information & Related Technology) is a risk governance framework, created by the Information Systems Audit and Control Association (ISACA).

There are five main components of COBIT:

- COBIT framework | Designed to help organisations organise and categorise all of their objectives when it comes to IT governance. It also helps companies following good practices of the IT domain and integrates it with the business requirements as a whole

- Process descriptions | Provide organisations with a process model and create a common language for all departments across the enterprise

- Management guidelines | Used to assign job roles and responsibilities for IT governance. This helps in creating a uniform structure across the company and helps departments work together and agree on their business objectives as well as to measure overall performance. The guidelines also showcase the relationship COBIT has with all other processes in the organisation

- Maturity models | Used to better understand the capability and maturity level of each process and work on any gaps found in the same

- Control objectives |Provide organisations certain requirements they need to meet so that they can manage their control of IT processes effectively in the company.

|

IA notes:

|

Part 3

This section provides you with generic questions to include in a high-level test plan.

|

1. Determine where the lines of responsibility are drawn between the business and IT. Question why, as appropriate: Are the set-up and maintenance of user accounts, functionality, standing data (eg, limits), parameters etc managed by the business? If not, why not? Similarly, does the responsibility for auditing the live business applications and the user side of IT projects sit in the first line? If not, why not? |

|

2. Are themed audit engagements, across departmental boundaries, feasible and occurring in your organisation? Consider whether audit scope is being restricted according to the organisation of your business and IT departments. |

|

3. Look for Systems Overview documentation, explaining the ‘what, why, who, how, when and where’ of your core processing in layman’s terms, including the flow of data between those systems.’ If this documentation is lacking, consider, how do employees gain the necessary understanding without it? |

|

4. Look for, and assess, the organisation’s IT strategy. This should specify, clearly and concisely, how the organisation’s IT strategy/plan will support the achievement of the organisation’s business objectives over a suitable period. The highest level of user management, IT management, and other key stakeholders should sign off the plan. |

|

5. Is an effective process in place to manage the organisation’s IT-related risk appetite? Consider: · the involvement and alignment of the business and IT in the process · the clarity of the processing objectives and the associated risks · reporting of IT-related risks and weaknesses to the risk committee and executive management. |

|

6. Consider, how does the Board gain ongoing assurance that systems are secure, compliant and processing as intended? |

|

7. Is the terminology employed during communication between IT and the users clearly understood? |

|

8. Has the business formally accepted that, regardless of the technology, third-parties and outsourcing employees, it owns the data, and is ultimately responsible for the achievement of its processing objectives? |

|

9. Does the business take day-to-day responsibility for the checks/reconciliations to confirm the achievement of the organisations processing objectives? |

|

10. Is the business appropriately involved in the definition of all business application user requirements, including systems security facilities, at the development stage? |

|

11. Are IT standards effective? Consider the degree of exceptions to the standards being identified (eg by Internal Audit, Risk, Cyber Security and IT) |

|

12. Is a methodology document or equivalent in place to explain to business and IT personnel, in simple terms, how the business applications and data will be secured? |

|

13. Is effective analysis being undertaken to identify and address the root causes of IT control weaknesses? |

|

14. Is data interrogation undertaken (eg to assess completeness and accuracy, and highlight trends)? If this is being undertaken by internal audit alone, consider whether this is appropriate based on available skills. |

|

15. Consider, in the case of every check that internal audit undertakes (or wishes to), is a similar check already being carried out within the business and, if not, why not? |

|

16. Is the business appropriately involved in the preparation, testing and sign-off of contingency/disaster recovery plans? |

|

17. Is effective change management exception reporting in place? |

|

18. Are IT vendors and third-party contracts subject to appropriate control/review? Consider: · assignment clauses, escrow agreements governing access to third-party source code, cross-border processing requirements etc · vendor suitability, compliance with your standards and values. |

|

19. Are IT budget/accounting processes subject to appropriate control/review? Consider how the IT budgets are set and monitored. |

|

20. Is end-user computing subject to effective control/review? Consider the appropriateness of IT facilities (such as spreadsheets and databases) that sit outside the control of IT function but may impact the organisation’s processing objectives. |

|

21. Are business user/audit personnel involved in any due diligence and divestiture exercises (if undertaken)? |

Conclusion

In the same way as you do not have to be a marketeer to audit marketing risks, you do not have to be an IT expert to audit IT risks.

Further reading

ISACA glossary is a useful reference guide for terminology and ‘buzz-words’